I present to you: Bride of the Creature from the Black Lagoon.

Happy Halloween, everybody!

I present to you: Bride of the Creature from the Black Lagoon.

Happy Halloween, everybody!

Director Autumn de Wilde (second from r.) and actors (l-r) Amber Anderson, Tanya Reynolds, Josh O’Connor and Johnny Flynn on the set of Emma., 2019. (Photo: Liam Daniel/Focus Features, Los Angeles Times)

Better late than never: Here are twenty-one new movies due to be released in theaters or via other viewing platforms this February, all of which have been directed and/or photographed by women. These titles are sure to intrigue cinephiles and also provoke meaningful discussions on the film world, as well as the world in general.

FEBRUARY 7: And Then We Danced (dir. Levan Akin) (DP: Lisabi Fridell) – The Landmark at 57 West synopsis: “A passionate tale of love and liberation set amidst the ultraconservative confines of modern Georgian society, And Then We Danced follows Merab (charismatic Levan Gelbakhiani), a talented and devoted dancer, frustrated by the rigid restrictions of his dance coach, who proclaims that there is no room for softness in a dance that ‘honors the spirit of the nation.’ Sensitive and headstrong, Merab has been training for years with his partner and best friend Mary (Ana Javakishvili) for a coveted spot in the National Georgian Ensemble, a potential escape from poverty and gateway to fame. The arrival of another male dancer, handsome Irakli (Bachi Valishvili)—gifted with perfect form and equipped with a rebellious streak—throws Merab off balance, sparking both an intense rivalry and a forbidden desire that may cause him to risk his future in dance as well as his relationships with Mary and his family. Sensual and romantic, And Then We Danced features spectacular, exciting dance sequences, as well as an unforgettable love story.”

FEBRUARY 7: Birds of Prey (And the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn) (aka Harley Quinn: Birds of Prey) (dir. Cathy Yan) – Salon review by Mary Elizabeth Williams: “The patriarchy will be dismantled with hand grenades and hair ties. At least, that’s the impression I have after watching the campy, ultraviolent, and feminist AF Birds of Prey (and the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn). Sounds like a practical plan.

“As Harley (Margot Robbie) explains in the film’s opening moments, the volatile former Dr. Harleen Frances Quinzel has recently broken up with her on-again, off-again supervillain boyfriend, Joker. She’s currently running through all the stages of relationship grief — crying, cutting her own hair, eating spray cheese, getting a hyena, feeding a pervert to the hyena, blowing up a chemical plant — you know, typical girl stuff. But she soon learns the dangers of no longer having a murdering, manipulative, emotionally abusive man around to protect her, and the power of women collaborating to unleash havoc.

“Four years ago, Robbie’s gleefully unhinged performance as Harley in Suicide Squad made her an immediate fan favorite, even if critics were less charitable about the film itself. Now, Gotham City is still teeming with antiheroes who posses potent combinations of brains, combat skills and total disregard for humanity. But there’s nobody else who, like Harley, understands that a foe’s list of grievances against them may include ‘has a vagina.’ Nor is there another who might let a sadistic goon reach into her pocket . . . and pull out a tampon. Or one who, in a climactic battle, will hand a fellow combatant a welcome hair thingy to pull back her tresses. You know how Ginger Rogers did everything Fred Astaire did, but backwards and in high heels? In case nobody every told you before, it was actually backwards, in high heels, menstruating, and with sweat-drenched hair flying in her face. And it’s pretty great to see that acknowledged, anywhere.

“Directed by Cathy Yan (Dead Pigs) and written by Christina Hodson (Bumblebee), “Birds of Prey” is at once a relatively formulaic, poop jokes and car chases-strewn comic book movie and a sophisticated exploration of contemporary feminist issues. Come for the ass kicking, stay for the takedown of rape culture.

“The villain this time around is crime lord/rich creep Roman Sionis (Ewan MacGregor, making some unusual accent choices), a sadistic nightclub owner trying to get his hands on a legendary diamond that holds a secret. When nimble young pickpocket Cassandra Cain (Ella Jay Basco) gets it first, Harley’s path inevitably crosses with that of the girl, as well as world-weary cop Renee Montoya (Rosie Perez, her dancer’s energy still gloriously full throttle), nightclub singer Dinah (Jurnee Smollett-Bell) and a mysterious vigilante known as the crossbow killer (Mary Elizabeth Winstead). Again and again, the message is clear — no dark knight in shining armor or maniac in clown makeup is coming to save any of them. Women, you’re on your own. But you’re stronger when you work together. And although the ladies are far from natural allies, they must eventually join forces to save their own lives, forming a kind of Gotham City Spice Girls.

“It’s uncanny how, in many ways, this technicolor popcorn opus traverses so much of the same ground Robbie’s recent Bombshell does. It also fits neatly into the growing pantheon of other post #MeToo stories, like this month’s The Assistant and the upcoming A Promising Young Woman (the latter of which Robbie is a producer on). It airlifts the audience out of the tired, convenient ideology around what a victim is supposed to look and act like. It demands you understand that a woman can be unsympathetic in many regards and still neither invite nor deserve harassment, abuse, and assault. Harley is at once a vicious, destructive lunatic and a traumatized survivor or a toxic relationship. She does terrible things. She is a violent criminal. She is vulnerable. (She’s also a professed Bernie voter, and if Harley Quinn can take time out of her chaotic day to register to vote, you can too.) This is not a story of her redemption, but her liberation.

“The film is pointed in its insistence on this point. In a pivotal early scene, Dinah notices a drunk Harley kissing a patron in the club’s alleyway and walks away, but when she realizes an incapacitated Harley is being lured into a van, she doubles back to intervene. Because if you can’t consent, it’s not consent. And in a moment chillingly reminiscent of a similar one in Bombshell, a powerful man demands a puzzled, then terrified, woman disrobe for him. Stung by a recent setback, Roman spies a club patron simply enjoying a night out and laughing with her friends. Goaded by his chief flunky, he flies into a rage, assuming the woman is laughing at him. As punishment, he makes her stand on a table in view of the whole audience, and orders her male companion take off her dress. It’s a shocking — and effective — interpretation of Margaret Atwood’s famed quote that men ‘are afraid women will laugh at them’ and women ‘are afraid of being killed.’ At the fan screening where I viewed the movie, the audience gasped at the scene, in part, I suspect, because director Yan entirely avoided making it sexual or exploitive. Think of every movie where a woman’s clothing has involuntarily come off, and how often it’s been played for laughs or thrills or smug comeuppance. (There are lists out there, but I’d rather not.) This is a middle finger to all that.

“While Birds of Prey doesn’t have the consistent whimsy of say, Deadpool, it is no two-hour downer. (It also doesn’t have T.J. Miller, thanks.) Plenty of the film’s tone is light, funny, and subtly paradigm-subverting — women complimenting other women for how well they fight in tight pants! Taking a beat to admire how well they kill bad guys! Shine theory, yo! Frankly, after months now of exhausting hot Joker takes and white male rage, a little feminine mayhem feels welcome right about now. Go see it and judge for yourself. Bring a friend. And don’t forget to pack a few extra hair bands for the revolution.”

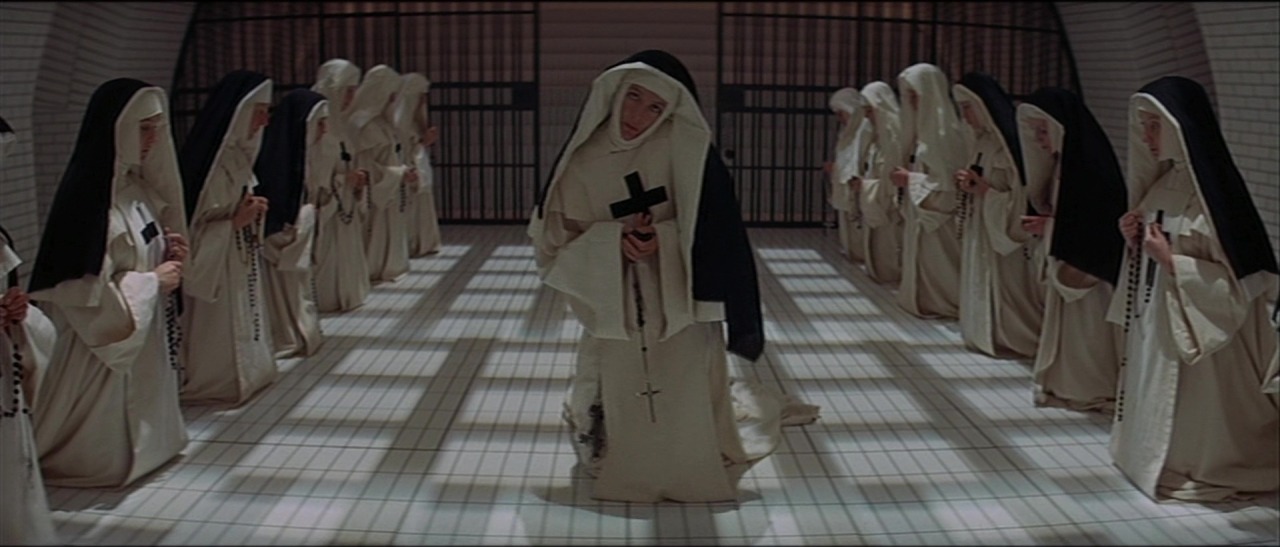

FEBRUARY 7: The Lodge (dirs. Severin Fiala and Veronika Franz) – Vulture’s Sundance Film Festival review by Emily Yoshida: “In The Lodge, faith is a kind of Chekhov’s gun, a potentially game-changing tool just lying there, waiting to be picked up by the wrong person. The faith in this case is of the Christian variety, and two mother figures — one straight-laced Catholic, the other a survivor of an Evangelical death cult — battle for control over it in the minds of their children. (It certainly adds to the tension that there is an actual gun in the scene as well.) As a psychological down-is-up horror movie, The Lodge has a few solid tricks up its sleeve. But when the smoke and mirrors clear, it’s ultimately a story about trauma, and a rather bleak one at that.

“Your heart kind of sinks for writer-directors Veronika Franz and Severin Fiala (Goodnight Mommy) in the opening moments of The Lodge, which include an empty interior that turns out to be a dollhouse, a frantic mother, and a head stuck out a car window. The eerie rhythms of the universe that gave us Deep Impact and Armageddon, Antz and A Bug’s Life, and Fyre and Fyre Fraud have conspired to make The Lodge exist in Hereditary’s shadow, but while some tonal and iconographic similarities exist, the two films jump off their shared diving board into very different corners of the psycho-mom pool.

“After a horrific opening gotcha to make sure you’re awake and paying attention, the film picks up with brother and sister Aidan (Jaeden Lieberher) and Mia (Lia McHugh) grieving the death of their mother Laura (Alicia Silverstone) and stubbornly refusing to meet their father Richard’s (Richard Armitage) girlfriend. They blame Grace (Riley Keough) for their mother’s suicide; she and their father had been separated for several years, but Laura killed herself the day he announced that he intended to remarry. Laura had an ardent Catholic faith, and the children hang on to her memory with equal fervor; Mia’s doll becomes a talisman of sorts for her memory. But, being children, they are eventually forced to spend Christmas at the family’s mountain lodge with their father and stepmom-to-be. We see them pack, all the essentials — sweaters, long johns … candles? Sea monkeys? — and hit the road.

“They have extra reason to be worried about Grace, especially after Googling her. Grace was made famous in the news as an adolescent, having been the only survivor of a cult suicide, and meant to spread the group’s apocalyptic message to the world. She seems perfectly nice in person, and even has a cute little dog that she brings along, but when we see her alone with Richard, she exhibits some signs of anxiety, and depends on a bottle of pills to keep her mental state regulated. She seems especially uneasy around the crosses left around the house by the late Laura, and a painting of the Virgin Mary in the dining room. Then Richard is called back to the city for work, and Grace and the children are left alone in the middle of nowhere, as a blizzard hits and snows them in.

“You may think you can guess where this film is going based on that description, but the interesting trick Fiala and Franz pull lies in a subtle shift in perspective. There’s no one moment in which it happens, but once we’re at the lodge, we soon realize that we’re watching things unfold from Grace’s point of view, and the children are the hostile forces with her in the house. When the power goes out and their belongings and provisions disappear, it doesn’t take long for some people’s grip on reality — including ours — to start slipping. As both the closest thing we have to a surrogate, and someone we’re not sure if we can trust ourselves, Keough’s performance walks a tricky line skillfully.

“The Lodge’s final reveal may feel like a bit of a deflation after all of the ominous elements it’s thrown together. Without giving away too much, it does feel as if Grace’s and Laura’s religion is a mere spooky prop for Fiala and Franz, an aesthetic theme to add mood and atmosphere to the increasingly desperate conditions in the house. But take away the religious themes and you still have an effectively chilling tale about how past experiences stay buried within us, and can never fully be defused.”

FEBRUARY 11 (on VOD): Senior Escort Service (dir. Shaina Feinberg) – Blu-ray.com synopsis: “Completely distraught after the sudden loss of her dad, filmmaker Shaina Feinberg will do anything she can to connect to him again. She catalogues her dad’s belongings – a calculator, a clock, a basket of lozenges. She forces her friends to wear his clothes and mimic his gestures. She takes a stab at making a webseries he’d always wanted to make – the name of which is ‘Senior Escort Service.’ And she combs through his journal, where she finds out about a process of dealing with grief that was invented by the grandchildren of Nazis. The process is called Familienaufstellung, which means Family Constellation, and it requires people to reenact their traumas as a means of making peace with it. This inspires Shaina to gather a group of women in a loft where they play out her trauma for her. Finally, in the hopes of singing her dad one last song, Shaina goes on a journey to his grave. On the journey, she recollects her dad’s love of acronyms, singing and ‘South Park,’ ultimately learning to live with his absence.”

FEBRUARY 12: Wild: Life, Death and Love in a Wildlife Hospital (dirs. Danel Elpeleg and Uriel Sinai) – Docaviv International Documentary Film Festival synopsis: “Patient-doctor relationships are always complex, but when the patient cannot talk or make decisions for himself it becomes particularly complicated. This is the everyday reality for the protagonists of this film: Ariella, a veterinarian, and Shmulik, the chief caretaker of a wildlife hospital. A parallel universe with its own questions and rules. Through love and Sisyphean labor they try to treat their patients, as they are confronted with issues that are also applicable to life outside the clinic walls. Is every life a life worth living? When does help ultimately prolong the suffering? And most of all, when is the right moment to let go?”

FEBRUARY 14 (in theaters & on VOD): Buffaloed (dir. Tanya Wexler) – Quad Cinema synopsis: “Director Tanya Wexler returns with a raucous comedy starring Judy Greer, Jai Courtney, Jermaine Fowler and Zoey Deutch (in a go-for-broke performance) that tracks one woman’s journey to finding her ethically dubious calling. As a young girl obsessed with making enough cash to get out of her blue-collar existence, Peg Dahl (Deutch) is betting on her sharp mind (and even sharper tongue) to get her into an Ivy League university. But a scalping scheme, brief stint in prison, and chance phone conversation with a debt collector change everything. As much an ode to the city of Buffalo as it is to the millions of Americans struggling with a seemingly dead-end economic existence, Buffaloed wrings hearty laughs out of a particularly timely and honest reality.”

FEBRUARY 14: First Lady (dir. Nina May) – Synopsis from the film’s official website: “First Lady is a romantic comedy about a woman, not married to the president, who runs for the office of First Lady. However, she winds up getting a much better proposal than she ever expected. She is torn between a promise and her calling.

“In this modern day fairytale, when President Morales (Joel King) dies in office, his widow, Kate (Nancy Stafford), agrees to help the VP, Taylor Brooks (Benjamin Dane), in his bid for the presidency. She must stop Mallory (Tanya Christiansen), the ditzy wife of their competitor, from destroying the dignity of the position. Kate and Taylor win, but their agendas butt heads and baby boomers clash with millennials while Mallory is determined to destroy Kate. Max (Corbin Bernsen), the prince of her youth, now, literally a King, comes back into her life, disguised as a bodyguard, making her a better offer than First Lady.

“First Lady is a modern fairytale for the whole family about an autumn romance with a twist. Nina May has written and directed a classic style romantic comedy that harkens back to a genre we all love. The story shows what could happen when two people lead successful lives apart and reunite later in life to find their happily ever after.”

FEBRUARY 14: I Was at Home, But… (dir. Angela Schanelec) – Film at Lincoln Center synopsis: “An elliptical yet emotionally lucid variation on the domestic drama, Schanelec’s latest film — which won her the Best Director prize at the 2019 Berlinale—intricately navigates the psychological contours of a Berlin family in crisis: Astrid—played with barely concealed fury by Maren Eggert—is trying to hold herself and her fragile teenage son and young daughter together following the death of their father two years earlier. Yet as in all her films, Schanelec develops her story and characters in highly unexpected ways, shooting in exquisite, fragmented tableaux and leaving much to the viewer’s imagination, hinting at a spiritual grace lurking beneath the unsettled surface of every scene.”

FEBRUARY 14 (in theaters & on VOD): The Kindness of Strangers (dir. Lone Scherfig) – Berlin International Film Festival synopsis: “Clara (Zoe Kazan) arrives in wintry New York with her two sons on the back seat of her car. The journey, which she has disguised as an adventure for her children’s sake, is soon revealed to be an escape from an abusive husband and father. He is a cop, and Clara is desperately trying to elude his attempts to pursue her. The three have little more than their car, and when this is towed away, they are left penniless on the street. But the big cold city shows mercy: in their search for refuge, the family meets a selfless nurse named Alice (Andrea Riseborough) who arranges beds for them at an emergency shelter. While stealing food at a Russian restaurant called ‘Winter Palace,’ Clara meets an ex-con, Marc (Tahar Rahim), who has been given the chance to help the old eatery regain its former glory. The ‘Winter Palace’ soon becomes a place of unexpected encounters between people who are all undergoing some sort of crisis and whom fate has now brought together. With a keen eye for character, Lone Scherfig explores human behaviour in extreme conditions. She depicts the harshness of life in the urban jungle, but she also demonstrates what can grow when strangers approach each other in friendship and with an open heart.”

FEBRUARY 14: Ordinary Love (dirs. Lisa Barros D’Sa and Glenn Leyburn) – Angelika Film Center synopsis: “Joan (Lesley Manville) and Tom (Liam Neeson) have been married for many years. There is an ease to their relationship which only comes from spending a life time together and a depth of love which expresses itself through tenderness and humour in equal part. When Joan is unexpectedly diagnosed with breast cancer, the course of her treatment shines a light on their relationship as they are faced with the challenges that lie ahead and the prospect of what might happen if something were to happen to Joan. Ordinary Love is a story about love, survival and the epic questions life throws at each and every one of us.”

FEBRUARY 14: The Photograph (dir. Stella Meghie) – Time review by Stephanie Zacharek: “Writer-director Stella Meghie’s romantic drama The Photograph is a lovely ghost of a movie, the kind of thing we used to call, in the days before the ascent of the superhero film, a popular entertainment. We get so few love stories today that it’s easy to forget they used to be a staple of the movie-release schedule; sometimes all you want is a chance to watch beautiful people meet, fall in love and break apart, only to be reunited (or not) in a way that feels gratifying. That’s what Meghie—whose credits include the comedies Jean of the Joneses (2016) and The Weekend (2018)—gives us here. The Photograph, both thoughtful and entertaining, with a pleasurably laid-back vibe, belongs to a class of movie that barely exists anymore on the big screen. It’s also a reminder that appealing actors are sometimes the best spectacle of all.

“The Photograph is really two entwined love stories, one set in the present, the other in the late 1980s. Lakeith Stanfield plays Michael, a reporter for a New York-based magazine. On assignment in New Orleans, reporting on the lingering effects of Hurricane Katrina and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on the area’s communities, he meets Isaac (Rob Morgan, in a fine, understated performance), a longtime resident with tales to tell. Isaac shows Michael a photograph of a woman he once loved, taken some 30 years earlier: This woman lounges in a regular kitchen chair, gazing at the camera’s lens, at us, with an uneasy mix of discontent and defiance. The subject of the photograph is a photographer herself, Christina (played, with radiant gravity, by Chanté Adams), who left Lousiana—and Isaac—for New York to pursue a dream career. Intrigued by the photograph, Michael sets out to learn more about Christina, and in the process meets her daughter, Mae (Issa Rae), a sophisticated museum curator. Mae isn’t sure she’ll ever be ready to commit to a guy, but we can see she’s as taken with Michael as he is with her. Shortly after their first meeting, he shows up at a museum event she hasn’t invited him to; their eyes meet, and the crowd of fancy-looking people milling about is virtually vaporized by the electricity between them. They flirt and share a first kiss. Later, weathering a Hurricane Sandy-like storm, they end up in bed. Both have their doubts about committing—Michael is still processing a recent breakup—but they also sense that the whatever-it-is that’s happening between them is worth exploring.

“There will, of course, be an event that drives them apart, as well as the revelation of a secret. Nothing in The Photograph will really surprise you. But surprise isn’t the point. Meghie is alive to the appeal of her actors and the easy chemistry between them. Rae, a marvelous comic actress, is somewhat restrained here, but she captures the essence of what it’s like to be a woman in the city, with a solid career, who sometimes just can’t turn off her BS detector. She gazes at Michael, with his liquid eyes and defense-melting earnestness, as if she can hardly believe he’s real. He seems to be presenting his soul to her in the smallest words and gestures, like the way he says, ‘I’m sorry’ when he learns her mother has recently passed away—Stanfield makes it all feel believable. The duo’s scenes together have an easy, loping rhythm. When Michael visits Mae’s apartment for the first time, and puts on the Al Green LP they’ve plucked from her mother’s things, your first impulse may be to roll your eyes at the obviousness of it all. But Meghie shapes the moment into a luxurious swoon. This is just how we want things to be, the way we’ve so often seen them in the movies. The Photograph captures the way people fall in love without meaning to, when they’re on their way to doing other things.

“It also features some terrific second bananas, among them Lil Rel Howrey as Michael’s brother, who’s not wrong when he says that stormy weather is the best ‘do-it’ weather. There are a few sex scenes in The Photograph, but they’re tender and discreet. Viewers are advised, however, that the movie pulls out the stops when it comes to fashion and New York City real-estate porn: Mae’s apartment is an urban palace with mile-high windows and a kitchen worthy of a cooking show. And the first time we see her, she’s wearing a voluminous trench coat in a black, white and brown graphic print, the kind of chic, daring gear you might dream of buying if you happen to land that important high-profile job—and if you don’t have to ride the subway ever again.

“Meghie takes pleasure in presenting that fantasy for us, the reverie of what it would be like to have great clothes, a cool job and a massive, gorgeous apartment. But she presents all of those things in movie language, not the vocabulary of a sterile Instagram feed. At times The Photograph feels like a modern version of a ‘30s Hollywood romance, where the heroine might live unapologetically in an all-white art deco apartment and wear marabou slippers while lounging. In other words, the trappings of Mae’s life feel earned, lived in and enjoyed, not presented solely to stoke envy and prove that she’s living her #bestlife. The boyfriend who loves her, almost instantly, for who she is—even while she’s still figuring out who she is—is also part of that fantasy. The Photograph is a story about the people we dream of being, people who find happiness despite mistakes they make along the way. It’s harder than it looks in the movies—but then, that’s why we need the movies. Vive the love story! And its power to make us believe, if only for a few hours, that maybe that could be us, too.”

FEBRUARY 14: Portrait of a Lady on Fire (dir. Céline Sciamma) (DP: Claire Mathon) – Slate review by Dana Stevens: “Why, Héloïse wants to know, does the portrait look so little like its subject? ‘There are rules. Conventions. Ideas,’ explains Marianne, unconvincingly. The face in the painting, Marianne’s first attempt at a portrait of Héloïse, is placid, rosy, and conventionally feminine in its inoffensive prettiness; the real Héloïse (Adèle Haenel), though even more beautiful, has an intimidatingly direct gaze and a serious, even somber demeanor. But given the purpose of the portrait—Heloïse’s mother plans to present it as a gift to the Italian nobleman whom Héloïse is to marry, sight unseen—it’s understandable why Marianne (Noémie Merlant) would soften Héloïse’s features and blunt the severity of her expression. In Céline Sciamma’s austere yet sensuous fourth feature Portrait of a Lady on Fire (which opens Friday in New York and Los Angeles before a wide release in February), this frequently altered painting becomes an index of the changing relationship between the two young women: At first distant, proper and ladylike, it slowly turns into something passionate, truthful, and almost unbearably intimate.

“Of course, another reason the portrait might not resemble Héloïse at first is because she never posed for it. Furious at her powerlessness to escape the arranged marriage, she walked out midsitting on the last artist who tried to paint her, leading him to destroy his work. Now her mother (Valeria Golino) tells Héloïse that Marianne has been brought in to be her companion on her daily cliffside walks; Marianne must soak in as much about Héloïse as she can on those walks, squirrel away sketches, and work on the portrait in private. There’s more backstory, but the information needed for the film’s stark setup is simple to grasp: two women, a canvas on an easel, a secret, the sea.

“The year, according to the production notes, is 1770, but no on-screen legend or other temporal marker clues us in to that date other than the women’s corseted floor-length dresses. The location is equally indeterminate: an isolated house on a high cliff by the ocean. (The film was shot on location on the coast of Brittany.) In the early scenes especially, the story seems to take place in a timeless, almost abstract space, like the films Ingmar Bergman shot with only a handful of actors on the Swedish island of Fårö. Though men appear, namelessly and briefly, at the beginning and end, Portrait of a Lady on Fire takes place almost completely in a world made up of women: the two leads, Heloïse’s mother, the young house servant Sophie (Luàna Bajrami), and in one scene a group of village women who sing a haunting a cappella song around a bonfire. But it’s the off-screen men who call all the shots in these women’s lives; those rules, conventions, and ideas that govern Marianne’s painting of an upper-class bride-to-be are the same ones responsible for Héloïse’s desperate sense of entrapment.

“To give away any more than the fact that the two women fall madly in love would be to deprive the viewer of Portrait of a Lady on Fire’s greatest pleasures: the stolen glances on cliffside walks, the conversations that end just as the truth is about to be spoken, the quiet contests of will over the content and meaning of that ever-changing canvas. Again and again Sciamma finds ways to deliver meaning cinematically rather than in words, whether through the placement of faces in the frame or a detail revealed obliquely in a mirror. In addition to being a swoon-worthy romance—a bodice-ripper in which corsets are not torn but slowly, lovingly unlaced—this is a meditation on feminism, art, and feminist art, as embodied by the portrait of the title but also by the embroidery being stitched by Sophie the housemaid—and, late in the film, by an extraordinary artistic collaboration the three young women undertake together. Without ever needing to spell it out, Sciamma makes clear that the weight of patriarchy means that this idyll by the sea may be these young women’s one chance to experience anything like real passion or freedom. That knowledge, on both the audience’s part and the lovers’, lends every moment of their time together—a fragment of music Marianne plays for Héloïse on the harpsichord, a shared reading of Ovid’s Metamorphoses—a kind of desperate poignancy.

“Adèle Haenel, the fierce-eyed, dark-browed beauty who plays Héloïse, may be familiar to audiences from her roles as an uncompromising AIDS activist in the 2017 French drama BPM or a young Belgian doctor in the Dardenne brothers’ The Unknown Girl. She’s also Sciamma’s romantic partner in real life and has already played the object of desire in the director’s debut film, Water Lilies. That real-life connection, whether you go in knowing about it or not, adds another layer to what’s on screen: the story of one woman attempting to render her love for another, not only with a paintbrush but with a camera. As Marianne, Noémie Merlant is also extraordinary: As she stands at the easel her huge dark eyes take in every detail of her beloved’s face, and though she didn’t do the painting herself (the portraits in the film are by the artist Hélène Delmaire), you completely believe she could have.

“Portrait of a Lady on Fire is that rare movie in which every choice feels thought through, meaningful, and right, from the costumes by Dorothée Guiraud to the cinematography by Claire Mathon. (When it comes to collaborating on feminist art, Sciamma walks the walk.) When the musical passage Marianne plays for Héloïse early in the film—the ‘Summer’ section of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons—returns at the end in its full orchestral glory, there’s a sense of inevitable, if tragic, completeness. Just like the short time the lovers have together, Portrait of a Lady on Fire is minimal but perfect, without an image, a glance, or a brushstroke to spare.”

FEBRUARY 14 (in theaters & on VOD): The Rest of Us (dir. Aisling Chin-Yee) – Toronto International Film Festival synopsis by Steve Gravestock: “Director Aisling Chin-Yee and screenwriter Alanna Francis make their mutual feature debut with this generous, slyly funny, and at times heartbreaking paean to a most unlikely female friendship. Cami (Heather Graham) is a children’s book author and illustrator who has been raising her surly and combative teenage daughter, Aster (2016 TIFF Rising Star Sophie Nélisse), on her own ever since her ex, Craig, abandoned them to start a new life with Rachel (Jodi Balfour). When an unforeseeable tragedy leaves Rachel and Tallulah (Abigail Pniowsky), the daughter she had with Craig, evicted and with no place to go, Cami steps in and offers to put them up in her rundown camper.

“Perhaps unsurprisingly, Cami and Rachel’s path to friendship is a rough one, what with years of simmering resentment constantly threatening to spill over. Those old tensions are exacerbated when both mothers hit it off with the other’s daughter, each offering quantities of understanding that the birth parent can’t. This already tenuous situation is even further complicated by the secrets that all concerned are hiding, even the outwardly saintly Cami.

“As unpredictable and recognizable as real life, The Rest of Us is propelled by a compassion for all of its characters (even when they behave badly), following them as they learn how to embrace life, how to be loyal, and how to forgive one another and themselves.”

FEBRUARY 21: Cabaret Maxime (dir. Bruno de Almeida) (DP: Lisa Rinzler) – Metrograph synopsis: “Michael Imperioli plays Bennie Gaza, the owner of Cabaret Maxime, a nightclub specializing in burlesque and striptease located in an old red-light district. Bennie is old school. He runs his business like a family operation, struggling to balance the individual needs of his performers with those of his manic-depressive wife—but the forces overseeing the gradual gentrification of the neighborhood are trying to squeeze him out, not stopping at the threat of violence. A finely shaded, character- driven thriller from Portuguese filmmaker de Almeida, providing Imperioli one of his richest film roles to date.”

FEBRUARY 21: Emma. (dir. Autumn de Wilde) – NPR review by Justin Chang: “The latest adaptation of Jane Austen’s Emma is as handsome, clever and rich as its famous heroine — and I mean ‘rich’ in the caloric sense, as well. I wanted to snack on every pastel-hued surface of Kave Quinn’s production design, which suggests nothing less than a frosted cupcake come to life — a feast of lace bonnets and high collars, gilded frames and glass chandeliers.

“Happily, all this decorative excess serves a purpose. This is the first feature from the photographer and music-video director Autumn de Wilde, and while she has an obvious eye for beauty, she has an equally sharp eye for the absurd. There’s a touch of Wes Anderson archness to her aesthetic, the way her camera both flatters and mocks the cavernous drawing rooms and sunny meadows of the 19th-century English village of Highbury. De Wilde knows that something as simple as a symmetrically framed shot of her characters can serve as a silent punchline. Her style is an ideal marriage of visual extravagance and satirical distance.

“Speaking of ideal marriages: Emma Woodhouse, the 21-year-old queen bee of Highbury, remains as irrepressible a matchmaker as ever. Anya Taylor-Joy, the actress with the piercing gaze who came to prominence in horror movies like The Witch, plays her as a somewhat chillier, more aloof heroine than, say, Gwyneth Paltrow did in 1996. But if anything, that only makes it all the more moving to see Emma’s porcelain-like facade crack as she realizes that her instincts as a judge of character were not as shrewd as she thought.

“Fortunately, her longtime family friend Mr. Knightley is there to scold and correct her at every turn. The actor and musician Johnny Flynn, so memorable in the psychological thriller Beast, brings a scruffy rock-star edge to the role of this impeccably well-mannered gentleman. The two of them spar furiously over the matter of Emma’s friend Harriet Smith, whom she’s trying to match up with the local vicar, Mr. Elton — a very funny Josh O’Connor, whom you may recognize as Prince Charles on The Crown. But Emma’s plans have a way of backfiring: Too late she realizes that the foolish Mr. Elton has fallen in love with her, not Harriet.

“The late English mystery writer P.D. James once wrote an essay championing Emma as not just a great piece of literature but also a great detective story — a series of deceptions and misunderstandings so cunningly crafted that both Emma and the reader are led up the garden path. By the end, order is happily restored and the truth is shown to have been hiding in plain sight, as Emma realizes how badly she misjudged everyone’s romantic motivations, including her own.

“If you’ve read the book or seen an earlier adaptation, you won’t be surprised by any of these revelations. The script, by the Booker Prize-winning novelist Eleanor Catton, is fairly faithful to the story and no less satisfying for it. This Emma isn’t an audacious reinterpretation like Greta Gerwig’s Little Women, which took significant liberties with a similarly beloved novel.

“OK, so some Austen purists might take issue with the early shot of Mr. Knightley’s naked backside as a servant helps him dress, or a later scene when Emma briefly lifts her skirt to warm her rear end by the fireplace. But I liked these moments of earthy humor. It’s de Wilde’s way of puncturing her characters’ pretensions, as if to remind us that they’re flesh-and-blood human beings beneath all that stately diction and period finery.

“After the effervescent comedy of the movie’s first half, the second is basically one emotional knockout punch after another, aided by a musical score that deftly balances whimsy and melancholy. It helps that de Wilde’s actors are so good at finding fresh nuances even in this timeless material. I loved every hilarious moment of Miranda Hart’s performance as Miss Bates, the village chatterbox whose stories bore Emma to no end — but who turns out to have the biggest heart in Highbury. Mia Goth is especially lovely as the naive, eager-to-please Harriet. And it should come as no surprise that the great Bill Nighy steals his every scene as Emma’s endearing hypochondriac of a father. He’s a perfect mascot for the movie — impeccably dressed, knowingly ridiculous and awfully hard to resist.”

FEBRUARY 21 (streaming on Netflix): The Last Thing He Wanted (dir. Dee Rees) – Sundance Institute synopsis: “Journalist and single mother Elena McMahon (Anne Hathaway) has rigorously investigated Contra activity in Central America for years. Frustrated when her coverage is censored, relief comes in an unexpected package: her acerbic father (Willem Dafoe) falls ill and leaves her a series of unfinished and unsavory arms deals in that very region. Now a pawn in a risky and unfamiliar game, surrounded by live ammunition in more ways than one, and alongside a U.S. state official (Ben Affleck) with whom she has a checkered past, Elena needs to parse her own story to survive. With her disenchanting life awaiting her back home, she is forced to consider what she really wants.

“Director Dee Rees (Pariah, Mudbound) is a Sundance Institute Vanguard Award winner and a lab fellow several times over, and she returns to the Sundance Film Festival with this adaptation of Joan Didion’s novel by the same name. Seasoned performances by Hathaway, Affleck, and Dafoe match the sobriety of the subject matter and convey the questionable intentions, inscrutable connections, and bitter fates of these complex characters.”

FEBRUARY 21 (on VOD): Manou the Swift (aka Birds of a Feather or Swift) (dirs. Andrea Block and Christian Haas) – Sola Media synopsis: “Manou (Josh Keaton) grows up believing he is a seagull like his parents (Kate Winslet, Willem Dafoe). He strives to swim, fish and fly like them but seems not very gifted. At Summer race he discovers Why. To his great shock he finds out he was adopted as an offspring of the much-hated Swifts. His family still stands by him, claiming he is a bird like them. Especially his seagull brother Luc (Mike Kelly) admires him wildly. One night Manou fails to guard the eggs and surrenders one to the rats. The seagulls are outraged and Manou is expelled from home. Utterly disappointed he retreats and stumbles across Percival (David Shaughnessy), a funny Guinea Fowl who cannot fly but turns out to be a deep-rooted pal. Manou checks out the swifts‘ way with his new buddies Yusuf (Yaron Mesika) and Poncho (Arif S. Kinchen) when he bumps into Kalifa, a stunning lady swift. Suddenly he is struck by an entangling flirt on top of all other troubles. Stakes are high as Rats hijack Swift eggs and a big Storm threatens the Seagulls. Manou is committed to save them both – courageous like a seagull and inventive like a swift.”

FEBRUARY 21 (in theaters & on VOD): Premature (dir. Rashaad Ernesto Green) (DP: Laura Valladao) – IFC Center synopsis: “On a summer night in Harlem during her last months at home before starting college, seventeen-year-old poet Ayanna (Zora Howard) meets Isaiah (Joshua Boone), a charming music producer who has just moved to the city. It’s not long before these two artistic souls are drawn together in a passionate summer romance. But as the highs of young love give way to jealousy, suspicion, and all-too-real consequences, Ayanna must confront the complexities of the adult world—whether she is ready or not.

“Emotionally raw, intimate, and honest, Premature is at once timeless and bracingly contemporary in its portrait of a young woman navigating the difficult choices that can shape a life.”

FEBRUARY 21 (streaming on Netflix): System Crasher (dir. Nora Fingscheidt) – Berlin International Film Festival synopsis: “Bernadette (Helena Zengel), or Benni as she prefers to be known, is a delicate-looking girl with unbridled energy. She is a ‘system crasher.’ This term is used to describe children who break every single rule; children who refuse to accept any kind of structure and who gradually fall through the cracks in Germany’s child and welfare services. No matter where this nine-year-old is taken in, she is booted out again after a short time. And that is exactly what she is after, because all she wants is to be able to live with her mother (Lisa Hagmeister) again: a woman who is totally unable to cope with her daughter’s incalculable behaviour.

“Made from her own multi-award-winning script, Nora Fingscheidt has created an intense drama about one child’s overwhelming need for love and security and the potential for violence that this engenders. At the same time, the film depicts the tireless attempts of educators and psychologists who use respect, trust and confidence to create a way forward for children who threaten to destroy others and themselves as a result of their unpredictable outbursts.”

FEBRUARY 28 (in theaters & on VOD): Disappearance at Clifton Hill (aka Clifton Hill) (dir. Albert Shin) (DP: Catherine Lutes) – Toronto International Film Festival synopsis by Ravi Srinivasan: “When Abby (Tuppence Middleton) returns to her hometown of Niagara Falls after her mother dies, she becomes obsessed with a fragmented memory from her childhood — a kidnapping she believes she was witness to. She is reunited with her estranged younger sister, Laure (Hannah Gross), and they attempt to settle their mother’s estate involving the sale of the family motel, but Abby’s compulsive desire to reconcile her past grows increasingly out of control.

“Clifton Hill is the highly anticipated third feature from Albert Shin, whose In Her Place was named to TIFF’s 2014 Canada’s Top Ten. Shin’s latest is an intense and taut psychological thriller that exposes the seedy underbelly of structural systems through the point of view of its dynamic female protagonists. Middleton delivers a stellar and complex performance as a woman obsessed with her troubled past while trying to uncover a crime to which she’s convinced she was an accomplice. Shin and co-writer James Schultz craft a sharp, suspenseful drama, equipped with twists and turns, culminating with a climax that will leave you thinking for days.

“Aided by an all-star cast — including an unforgettable appearance from David Cronenberg — Shin looks behind an idyllic tourist town and finds a questionable community with a history as sordid as the characters who inhabit it.”

FEBRUARY 28: A Fine Line (dir. Joanna James) – Cinema Village synopsis: “A Fine Line is an award winning documentary that explores why less than 7% of head chefs and restaurant owners are women hearing candid insights from world-renowned female chefs, including: first and only Three Michelin Star chef in the U.S. Dominique Crenn, Emmy Award winning TV host Lidia Bastianich, first female Iron Chef Cat Cora, one of Time Magazine’s Most Influential People Barbara Lynch, Two Michelin Star Chef April Bloomfield, World’s Best Chef Daniel Humm and more. A central narrative unfolds of a small-town restaurateur and single mother on a mission to do what she loves while raising two kids with the odds stacked mightily against her. The film gets to the heart of what is needed to empower women across all industries, by following the personal story of this every day hero, Valerie James. A Fine Line opens up a timely conversation about gender equality, women leadership and diversity in the culinary field and beyond.”

Best Picture: Parasite

Best Director: Sam Mendes (1917)

Best Actress: Renée Zellweger (Judy)

Best Actor: Joaquin Phoenix (Joker)

Best Supporting Actress: Laura Dern (Marriage Story)

Best Supporting Actor: Brad Pitt (Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood)

Best Original Screenplay: Bong Joon Ho and Han Jin Won (Parasite)

Best Adapted Screenplay: Taika Waititi (Jojo Rabbit)

Best Cinematography: Roger Deakins (1917)

Best Editing: Jinmo Yang (Parasite)

Best Production Design: Nancy Haigh and Barbara Ling (Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood)

Best Costume Design: Jacqueline Durran (Little Women)

Best Hair & Makeup: Bombshell

Best Sound Editing: 1917

Best Sound Mixing: 1917

Best Visual Effects: 1917

Best Original Score: Hildur Guðnadóttir (Joker)

Best Original Song: “(I’m Gonna) Love Me Again” (Rocketman)

Best International Feature Film: Parasite (South Korea)

Best Animated Feature: Toy Story 4

Best Documentary: American Factory

Best Animated Short Film: Hair Love

Best Live Action Short Film: Brotherhood

Best Documentary Short Subject: Learning to Skateboard in a Warzone (If You’re a Girl)

Here we are once again, on the eve of the Oscar nomination announcement. Tomorrow morning we will discover who has received Hollywood’s most prestigious honors at the 92nd annual ceremony. Some categories, like Best Director, are extremely difficult to guess accurately. A few predictions may seem like dark horses, but I figured I would go with my gut rather than choose some of the more obvious possibilities. (Particular apologies to Zhao Shuzhen from The Farewell, since I don’t expect her to be recognized by the Academy; if she is nominated, I’ll be overjoyed!) Also, FYI: I don’t predict the three short film categories at this stage since I never have any clue about those until after the nominations come out. Here are my picks:

Best Picture: Bombshell; The Irishman; Jojo Rabbit; Joker; Little Women; Marriage Story; 1917; Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood; Parasite

Best Director: Martin Scorsese (The Irishman); Taika Waititi (Jojo Rabbit); Sam Mendes (1917); Quentin Tarantino (Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood); Bong Joon Ho (Parasite)

Best Actress: Charlize Theron (Bombshell); Awkwafina (The Farewell); Renée Zellweger (Judy); Saoirse Ronan (Little Women); Scarlett Johansson (Marriage Story)

Best Actor: Joaquin Phoenix (Joker); Adam Driver (Marriage Story); Leonardo DiCaprio (Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood); Antonio Banderas (Pain and Glory); Taron Egerton (Rocketman)

Best Supporting Actress: Jennifer Lopez (Hustlers); Scarlett Johansson (Jojo Rabbit); Florence Pugh (Little Women); Laura Dern (Marriage Story); Margot Robbie (Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood)

Best Supporting Actor: Tom Hanks (A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood); Al Pacino (The Irishman); Joe Pesci (The Irishman); Brad Pitt (Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood); Song Kang-ho (Parasite)

Best Original Screenplay: Lulu Wang (The Farewell); Rian Johnson (Knives Out); Noah Baumbach (Marriage Story); Quentin Tarantino (Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood); Bong Joon Ho and Han Jin Won (Parasite)

Best Adapted Screenplay: Steven Zaillian (The Irishman); Taika Waititi (Jojo Rabbit); Todd Phillips and Scott Silver (Joker); Greta Gerwig (Little Women); Anthony McCarten (The Two Popes)

Best Cinematography: Rodrigo Prieto (The Irishman); Lawrence Sher (Joker); Jarin Blaschke (The Lighthouse); Roger Deakins (1917); Robert Richardson (Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood)

Best Editing: Andrew Buckland and Michael McCusker (Ford v Ferrari); Thelma Schoonmaker (The Irishman); Lee Smith (1917); Fred Raskin (Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood); Yang Jin-mo (Parasite)

Best Production Design: Regina Graves and Bob Shaw (The Irishman); Mark Friedberg and Kris Moran (Joker); Jess Gonchor and Claire Kaufman (Little Women); Nancy Haigh and Barbara Ling (Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood); Dennis Gassner and Lee Sandales (1917)

Best Costume Design: Ruth E. Carter (Dolemite Is My Name); Christopher Peterson and Sandy Powell (The Irishman); Jacqueline Durran (Little Women); Arianne Phillips (Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood); Julian Day (Rocketman)

Best Hair & Makeup: Bombshell; Dolemite Is My Name; Joker; Judy; Rocketman

Best Sound Editing: Avengers: Endgame; Ford v Ferrari; 1917; Rocketman; Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker

Best Sound Mixing: Avengers: Endgame; Ford v Ferrari; 1917; Rocketman; Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker

Best Visual Effects: Avengers: Endgame; The Irishman; The Lion King; 1917; Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker

Best Original Score: Michael Giacchino (Jojo Rabbit); Hildur Guðnadóttir (Joker); Alexandre Desplat (Little Women); Randy Newman (Marriage Story); Thomas Newman (1917)

Best Original Song: “Into the Unknown” (Frozen II); “Stand Up” (Harriet); “Spirit” (The Lion King); “(I’m Gonna) Love Me Again” (Rocketman); “Glasgow (No Place Like Home)” (Wild Rose)

Best International Feature Film: Atlantics (Senegal); Beanpole (Russia); Les Misérables (France); Pain and Glory (Spain); Parasite (South Korea)

Best Animated Feature: Frozen II; How to Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World; I Lost My Body; Missing Link; Toy Story 4

Best Documentary: American Factory; Apollo 11; For Sama; Honeyland; One Child Nation

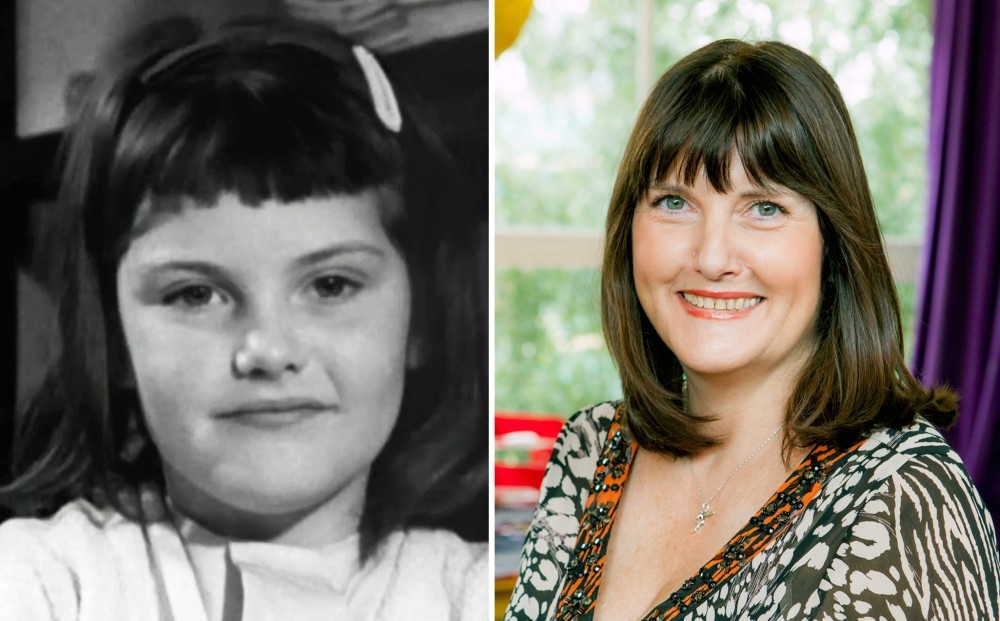

Actress Brooklynn Prince and director Floria Sigismondi on the set of The Turning, 2018. (Photo: Twitter)

Here are eighteen new movies due to be released in theaters or via other viewing platforms this January, all of which have been directed and/or photographed by women. These titles are sure to intrigue cinephiles and also provoke meaningful discussions on the film world, as well as the world in general.

JANUARY 1 (streaming on Netflix): Ghost Stories (dirs. Zoya Akhtar, Dibakar Banerjee, Karan Johar and Anurag Kashyap) – Netflix synopsis: “The directors of Emmy-nominated Lust Stories (Zoya Akhtar, Anurag Kashyap, Dibakar Banerjee and Karan Johar) reunite for this quartet of thrillers.”

JANUARY 3: Advocate (dirs. Philippe Bellaiche and Rachel Leah Jones) – Quad Cinema synopsis: “Lea Tsemel defends Palestinians: from feminists to fundamentalists, from non-violent demonstrators to armed militants. As a Jewish-Israeli lawyer who has represented political prisoners for five decades, Tsemel, in her tireless quest for justice, pushes the praxis of a human rights defender to its limits. Advocate follows Tsemel’s caseload in real-time, including the high-profile trial of a 13-year-old boy—her youngest client to date—while also revisiting her landmark cases and reflecting on the political significance of her work and the personal price one pays for assuming the role of “devil’s advocate.” Tsemel spoke truth to power before the term became trendy and she’ll continue to do so after fear makes it unfashionable.”

JANUARY 3 (re-release): One Child Nation (dirs. Nanfu Wang and Jialing Zhang) (DPs: Yuanchen Liu and Nanfu Wang) – Cinema Village synopsis: “After becoming a mother, a filmmaker uncovers the untold history of China’s one-child policy and the generations of parents and children forever shaped by this social experiment.”

JANUARY 7 (streaming on Netflix): Live Twice, Love Once (aka Vivir Dos Veces) (dir. Maria Ripoll) (DP: Núria Roldos) – Netflix synopsis: “When Emilio (Oscar Martínez) is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, he and his family embark on a quest to reunite him with his childhood crush.”

JANUARY 10 (in theaters), JANUARY 28 (on VOD): Afterward (dir. Ofra Bloch) – City Cinemas Village East Cinema synopsis: “Jerusalem-born trauma expert Ofra Bloch forces herself to confront her personal demons in a journey that takes her to Germany, Israel and Palestine. Set against the current wave of fascism and anti-Semitism sweeping the globe, Afterward delves into the secret wounds carried by victims as well as victimizers, through testimonies ranging from the horrifying to the hopeful. Seen as a victim in Germany and a perpetrator in Palestine, Bloch faces those she was raised to hate as she searches to understand the narratives of the Holocaust and the Nakba, violent and non-violent resistance, and the possibility of reconciliation.”

JANUARY 10: Chhapaak (dir. Meghna Gulzar) – AMC Theatres synopsis: “Malti (Deepika Padukone) was attacked with acid on a street in New Delhi, in 2005. Through her story, the film makes an attempt to understand the on-ground consequences of surviving an acid attack in India, the medico-legal-social state of affairs that transpires after the acid has been hurled and the face is irreparably burnt.”

JANUARY 10: Liberation (dirs. Xiaoyang Chang and Shaohong Li) – Far East Films synopsis: “Based on real life events, the film is set in January 1949 and follows a group of soldiers involved in the final stages of the Battle of Pingjin. The cast includes Wallace Chung, Elane Zhong, Zhou Yiwei, Philip Keung, and Yang Mi.”

JANUARY 10: Tanhaji: The Unsung Warrior (dir. Om Raut) (DP: Keiko Nakahara) – AMC Theatres synopsis: “Tanhaji Malusare was an unsung Maratha warrior during the 17th century Maratha Empire, whose acts of valor and bravery continued to inspire soldiers long after his death in battle. He was endowed with a body of steel, courage of a lion with an agile mind and Chhatrapati Shivaji’s closest aide and trusted lieutenant. Ready to lay down his life for his King and country, this brave heart went to war, armed with a few Maratha soldiers to get back the Kondana Fort against the Mughal army headed by Udaybhan. Mughal’s had muscle power, but Tanhaji had sharp acumen. Unfortunately, Marathas won Kondhana Fort, but lost their Lion. Tanhaji left behind a void that none in history could ever fill. Tanhaji: The Unsung Warrior is a visual extravaganza that depicts the life and times of this unsung warrior, whose valor still makes the Nation proud.”

JANUARY 10: The Woman Who Loves Giraffes (dir. Alison Reid) (DPs: Dale Hildebrand, Lainie Knox and Iris Ng) – Quad Cinema synopsis: “In 1956, four years before Jane Goodall immersed herself in the world of chimpanzees, 23-year-old biologist Anne Innis Dagg made an unprecedented solo journey to South Africa to study giraffes in the wild. In this enlightening and inspiring documentary, the now-86-year-old retraces her groundbreaking steps with the help of old letters and stunning, original 16mm film footage. The intimate window into Dagg’s life as a young woman—and the world’s first ‘giraffologist’ whose research findings formed the foundation for many modern scientists —is juxtaposed with a first-hand look at the devastating reality that giraffes are facing today to create a bracing impact.”

JANUARY 16 (streaming on Netflix): Jezebel (dir. Numa Perrier) – Eye for Film’s SXSW review by Jennie Kermode: “Sex cam work is often portrayed as shameful, something only desperate women do and something that is bound to lead to unhappiness, yet – at least prior to the passing of the SESTA/FOSTA Act in the US – it revolutionised sex work, making it much safer by enabling people who had been out on the streets to earn a living from a virtual space. Numa Perrier’s beautifully observed drama Jezebel tells the story of one young woman whose life is transformed by it in a positive way.

“Perrier plays Sabrina, a phone sex worker with a young daughter, deadbeat boyfriend and home full of hangers-on to support. She has also made space for her younger sister Tiffany (Tiffany Tenille), whose life as a full time carer abruptly changes when their ailing mother is hospitalised. At the same time as dealing with the complicated emotions this brings, Tiffany needs to find a new way to make a living, so Sabrina persuades her to pursue an opportunity in sex camming, for which purpose the younger woman reinvents herself as Jezebel.

“The taboo of taking one’s clothes off in a forbidden space is always scariest the first time. Jezebel hesitates when doing it in front of the boss, but only briefly. Starting the same day means there’s no time for worry to build up, and the boss’ sister, who also performs there, takes her through the basics in a friendly and supportive way. To be clear, there’s no actual sex involved in this, though certain acts are simulated – with much laughter when the clients aren’t there – in order to increase earnings. As Jezebel comes to understand how much of it is about trickery and play, she loses her fear – but it’s as she starts to take control of her own sexuality that she really finds her strength, both at work and elsewhere in life.

“This is a film that never takes the easy route of eroticising its subject for the audience. Yes, it includes upper body nudity and we see the women at the cam business posing for clients, but their activity is very much presented as work, with a lot of humour at the expense of clients who take it seriously. Nevertheless, Jezebel gets to know some of her clients and forms a particular bond with a foot fetishist called Bobby (voiced by Brett Gelman), who changes the way she thinks about herself.

“It’s not all fun. A scene in which Jezebel is confronted with racism and has to try and explain to her white colleagues why a particular slur is not equivalent to the misogynistic insults they take in their stride is tough to watch, and has implications right across the service sector. There’s an acknowledgement of the nastier side of the internet and the way that the economic interests of the people least likely to face serious abuse there – also the people who have the most money and social status to begin with – act to resist attempts to fix it. We also see the strife that develops as the relationship between Jezebel and Sabrina changes, and the sniping the former has to put up with from the men in the household.

“Despite all this, this is a warm-hearted and positive story about a young woman taking control of her life, and it’s refreshing to see such stories being told about working class women in stigmatised professions. Shot close-up to emphasise the cramped spaces in which its heroine lives and works, it invites the viewer to share her delight as the world opens up to her.”

JANUARY 17 (in theaters & on VOD): The Host (dir. Andy Newbery) (DP: Oona Menges) – From a First Showing article by Alex Billington: “A disturbing tale of a London banker and an unassuming Dutch femme fatale, The Host follows Robert Atkinson (Mike Beckingham) and Vera Tribbe (Maryam Hassouni), two strangers with dark and disturbing secrets. When Robert flees London with a briefcase of stolen money, he seeks refuge in Amsterdam at Vera’s home. As they try to suppress their inner demons, a course of destruction emanates from their hidden secrets that can never be escaped.”

JANUARY 17 (streaming on Amazon Prime Video): Troop Zero (dirs. Bert & Bertie) – Seattle International Film Festival synopsis: “In 1977, the Voyager spacecraft was launched into the cosmos with a gold-plated record, conveying a playlist that best represented humanity and the Earth, a message to anyone who might be out among the stars. And, in Troop Zero, quirky nine-year-old Christmas Flint, played by the charismatic McKenna Grace (Gifted; I, Tonya), is set on getting her voice on that recording. Her way in: the 1977 Birdie Scout Jamboree, where a select troop’s vocalizing will be featured on the recording. But when rural Georgia’s demure Troop 5, led by the judgmental Miss Massey (Allison Janney), won’t have her, Christmas must start her own troop—with a down-to-earth Viola Davis by her side—and assemble an unorthodox team, despite Miss Massey’s best attempts to disqualify the underdogs. Cue shenanigans and a lively David Bowie-infused soundtrack. Add comedian Jim Gaffigan to the mix as Christmas’s hapless attorney father, and Troop Zero promises to be a sweet, silly, family-friendly comedy-drama with a warmhearted message of acceptance and the power of friendship. In their sophomore feature, premiering on the closing night of [last] year’s Sundance Film Festival, female co-directing duo Bert & Bertie bring us an irresistibly fun and touching celebration of unconventionality.”

(set photo; no production stills have been released yet, as far as I can tell)

JANUARY 24: Run (dir. Aneesh Chaganty) (DP: Hillary Spera) – From a Slash Film article by Ben Pearson: “Aneesh Chaganty, the co-writer/director of last year’s computer screen mystery Searching, is following up that movie with a more traditionally-filmed thriller called Run. Sarah Paulson (Glass, ‘American Horror Story’) stars opposite newcomer Kiera Allen.

“…Run follows a smart, cool teenager known as ‘Daughter’ (Allen) who uses a wheelchair and is raised in complete isolation by ‘Mother’ (Paulson), and the girl slowly learns that her mother is keeping a sinister secret.”

JANUARY 24: The Turning (dir. Floria Sigismondi) – Synopsis from the film’s official website: “For more than 100 years, a deeply haunting tale has been passed down to terrify audiences. DreamWorks Pictures’ The Turning takes us to a mysterious estate in the Maine countryside, where newly appointed nanny Kate is charged with the care of two disturbed orphans, Flora and Miles. Quickly though, she discovers that both the children and the house are harboring dark secrets and things may not be as they appear.

“Inspired by Henry James’ landmark novel, the haunted-house thriller is directed by spellbinding visualist Floria Sigismondi (The Runaways, Hulu’s ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’) and stars Mackenzie Davis (Terminator: Dark Fate, The Martian), Finn Wolfhard (It, Netflix’s ‘Stranger Things’), newcomer Brooklynn Prince (The Florida Project) and Joely Richardson (Red Sparrow, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo).”

JANUARY 29: Beanpole (dir. Kantemir Balagov) (DP: Kseniya Sereda) – IONCINEMA’s Cannes Film Festival review by Nicholas Bell: “In the words of Plato, “Only the dead have seen the end of war.” Such seems the case for the survivors left to pick-up the pieces in 1945 Leningrad during the first autumn after the end of WWII in Kantemir Balagov’s strikingly astute sophomore feature, Beanpole. Following two years on the heels of an equally impressive debut, 2017’s Closeness (which detailed a heinous kidnapping in late 90’s Nalchik, from whence he is from), Balagov goes further into the past to examine the lives and friendship of two Russian women struggling to move forward during the construction of Leningrad, which suffered one of worst sieges in history. Based loosely on Nobel Laureate Svetlana Alexievich’s book The Unwomanly Faces of War, Balagov co-wrote with scribe Aleksandr Terekhov (of Aleksey Uchitel’s 2017 Mathilde) a formidable psychological portrait of two women matched by the aching ferocity of two superb cinematic debuts from leads Viktoria Miroshnichenko and Vasilisa Perelygina.

“Many of the more popular international cinema dealing with the reconstruction period of post-WWII tends to center on the rise of survivors (usually male protagonists) through the rubble of Germany—but two unforgettable Nina Hoss performances come to mind dealing specifically with this time and location in 2008’s Anonyma and 2014’s Phoenix.

“Balagov grasps the mantle of his Russian predecessors with Beanpole, a haunting, visually striking depiction of women’s roles during reconstruction. Miroshnichenko is galvanizing as Iya, her nickname the titular period slang to describe her gangly frame (which is treated to a much more graceful comparison in the French subtitle translation as La Girafe). Suffering from debilitating spasms diagnosed as ‘post-concussion syndrome,’ which would later come to be recognized as PTSD, Iya is a broken soul working as a nurse in a Leningrad hospital.

“Having developed a warm relationship with her superior, Iya is designated as a literal Angel of Death, secretly assisting in euthanizing patients who will not recover from their wartime wounds, desiring to die. Likewise, the first act’s supreme tragedy involves the accidental death of the child, Pashka (Timofey Glazkov), who we initially assume belongs to Iya. Suddenly, Masha (Perelygina) arrives, the mother of the child who entrusted her son to her best friend so she could stay behind on the front lines and avenge the death of the child’s father. Upon learning of Pashka’s death, her reaction is to go out dancing, the rationale being she needs to work on having another baby. In Masha’s mind, a child will allow her to heal from the trauma inflicted by the war. However, it seems Masha’s internal scars have left her sterile—and so Iya is tasked with producing the salve which will assuage their passage to a brighter future.

“Both Iya and Masha are color coded as red and green (colors representing rebirth and wounds/war), designs which complement one another, begin to infiltrate, and eventually shift between the women as their vulnerabilities and resiliencies fluctuates. As the title indicates, Iya’s height (note, her name means violet in Greek, a color which requires two primaries to mix together) hints at Balagov’s subtexts regarding reconstruction, specifically women’s bodies and how they are allowed to move about in space or claim agency. Iya’s ungainliness paints her as the beautiful swan who was never able to realize she was no longer an ugly duckling.

“Beautifully textured cinematography from Kseniya Sereda captures a tremendously vibrant color palette of these period interiors, flanked by the less colorful but grainy exteriors of a bedraggled but bustling Leningrad (where a near-Anna Karenina moment occurs). Balagov concocts a third tremendous debut from Ksenia Kutepova, a remnant of a downgraded oligarchy whose son desires to marry Masha—Kutepova walks away with one of the film’s best moments as she highlights the underbelly of the façade afforded privileged woman (also of note, Olga Dragunova of Closeness appears in a minor role as a surly seamstress).

“Balagov pointedly avoids any direct mention of Stalin or Lenin, whose visual representations are also absent from Beanpole. However, his film channels the energies of some of Russia’s greatest filmmakers, with a mise en scene recalling Aleksey German’s classic My Friend, Ivan Lapshin (1985), which depicts the effects of Stalin’s 1930s purge on a small town in Russia. However, Beanpole plays like a sister film to Larisa Shepitko’s underrated and unforgettable 1966 film Wings, wherein a female ex-fighter pilot cum school teacher cannot find meaning in her life during peace time. Tragic, hopeful and subversive (the film paints a complex portrait of friendship and sexuality which would have been impossible to make in Russia), Beanpole confirms Balagov’s stature as a major contemporary filmmaker.”

JANUARY 31: The Assistant (dir. Kitty Green) – IndieWire’s Telluride Film Festival review by Eric Kohn: “Harvey Weinstein doesn’t appear in The Assistant, and nobody mentions him by name, but make no mistake: Director Kitty Green’s urgent real-time thriller marks the first narrative depiction of life under his menacing grip. ‘Ozark’ breakout Julia Garner is a revelation as the fragile young woman tasked with juggling the minutiae of the executive’s life, arranging a never-ending stream of airplane trips, staving off angry callers, and picking up the trash left in his wake.

“Beyond a few unfocused glimpses of a hulking figure roaming his office in the background, the Weinstein of The Assistant is a phantom menace who barrels down on the young woman’s life, but this fascinating psychological investigation doesn’t allow him to hijack a story that belongs to her. The Assistant doesn’t document the specifics of Weinstein’s abuses recounted by so many over the past two years; instead, it explores the harassment and control that kept his unwitting enablers under his grip.

“Green’s first fiction feature following the innovative true-crime documentary Casting JonBenét feels like a natural extension of her earlier work. Built out of immaculate research into the working conditions under Weinstein and how they affected many of the young women on its payroll, the movie unfolds as a gradual accumulation of intricate details, mapping out the character’s exhausting routine until it becomes her own private Twilight Zone. The Assistant adopts such a gradual pace that it sometimes works against the stunning performance at its center, but there’s no doubting the hypnotic power of a movie that digs inside Weinstein’s harrowing reign and observes the mechanics that allowed it to last so long. A quiet work with major ambitions, The Assistant is a significant cultural statement in cinematic form.

“As Jane, Garner delivers a masterclass of small, uncertain gestures. A Northwestern grad who harbors dreams of producing movies, she’s already enmeshed in an endless work cycle as the movie begins: Hopping out of her Astoria home before the sun rises, polishing up the vacant office, speeding through emails, printing out price sheets, and so on; the rest of the company slowly comes to life around her. Green constructs the atmosphere with a masterful focus on fragments of business talk, the clacking of keyboards, and ringing phones that draw out the drab nature of Jane’s work: She’s at once at the center of the action and entirely removed from it.

“And that includes the activities of her invisible boss, who only seems to notice her when she screws up. It doesn’t take long: After angering some moody client, Jane gets a call from her unseen overlord as fragments of his bitter tirade (‘They told me you were smart’) are barely audible. The specifics matter less than the way the abuse plays out on Garner’s face as she sinks into her hands, and the formal procedure that follows is just a few steps shy of a dark joke: The pair of unnamed male assistants (Noah Robbins and Jon Orsini) who sit across from Jane and judge her every move assemble behind her to dictate an apology email, and Jane does as she’s told. As much as The Assistant involves the process through which one man exerts control over a woman trapped by his direction, it also shows how the toxic workplace infects others in its grasp.

“As the physical toil of Jane’s work piles up — cleaning dishes, taking out the garbage, dealing with paper cuts — she begins to notice the evidence of Weinstein’s worst crimes. The offhand discovery of an earring piques Jane’s interest, as does a passing comment from one of the men at the company that nobody should ever sit on the office couch. Green makes the brilliant gamble of letting audiences pick up the pieces. With time, it becomes clear that Jane sees no recourse but to contend with circumstances that have since become a matter of grotesque public record.

“For a while, The Assistant seems as though it could simply hover in Jane’s world for hours, as if presenting the #MeToo equivalent of Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman. But then the movie injects a subtle plot twist, as Jane’s suddenly tasked with taking a young new assistant (Kristine Froseth) to her own hotel room. The wide-eyed Ohio transplant’s sudden A-list treatment confounds Jane, who seems as if she’s in denial about her boss’ real agenda with the young woman, and instigates a visit to the company HR office that pitches the movie into a whole new level of discomfort. Played by ‘Succession’ star Matthew Macfadyen, the executive tasked with belittling Jane for her complaint magnifies the way the company exerted control over their liabilities and how they got away with it. The backlash Jane experiences from her small attempt to take charge is devastating, and it ends with a sudden email from her boss that gives her just enough encouragement to keep her in line.

“The Assistant pads out so much of its 85-minute runtime with eerie textures that it tends to linger on the same note of despair, and it struggles to move the story into a new place by its closing act. The tension dissipates as The Assistant drifts toward its finale, and there’s a lingering sense that it underserves Jane’s story by basking so much of the company’s happenings in total mystery. It’s hard not to imagine what Green, whose previous work has used reenactments and voiceover to immerse viewers in real events, might have accomplished if she’d paired these scenes with real accounts from Weinstein’s victims.

“On the other hand, The Assistant doesn’t need to overstate the nature of Jane’s conundrum. Best appreciated as an experimental narrative about workplace oppression, it’s a fascinating illustration of how the worst abuses can remain hidden even from those closest to the lion’s den. Green has not set out to make the definitive retelling of the Weinstein scandal, the reporting on his years of sexual abuse and coverups, or the fallout that destroyed his company. (Brad Pitt’s Plan B already has that project in development.) Instead, the movie hovers in silent moments when taking action simply doesn’t seem feasible. The absence of payoff only adds to the haunting spell, and imbues the drama with purpose. Amid galvanizing stories about what it took to speak out, The Assistant is an essential reminder of why it took so long for the world to hear about it.”

JANUARY 31: The Rhythm Section (dir. Reed Morano) – Paramount Pictures synopsis: “Blake Lively stars as Stephanie Patrick, an ordinary woman on a path of self-destruction after her family is tragically killed in a plane crash. When Stephanie discovers that the crash was not an accident, she enters a dark, complex world to seek revenge on those responsible and find her own redemption.”

JANUARY 31 (streaming on Netflix): 37 Seconds (dir. HIKARI) – Toronto International Film Festival synopsis by Giovanna Fulvi: “Thirty-seven seconds without breathing at the time of her birth was all it took for Yuma (Mei Kayama) to develop cerebral palsy. For the physically restricted 23-year-old, those brief moments have shaped the course of her life. They take on additional significance near the end of HIKARI’s original and accomplished debut feature, when another burning revelation carries the unsettling disclosure of a family secret.

“Imaginative and sincere, the film follows the joys and pains of Yuma’s slow process of empowerment. Surprising narrative turns chart her emancipation from the protection and exploitation she experiences at the hands of the most important people in her life, an overprotective mother (Misuzu Kanno) and Sayaka (Minori Hagiwara), a blogger and influencer who passes Yuma’s work off as her own. A brilliant mangaka, Yuma has a vivid visual imagination. Although she can’t walk, she can draw, creating amazing stories as the driving force behind Sayaka’s success — the social stigma around Yuma’s physical disability preventing the acknowledgment of her talent. When an unprejudiced publisher of manga porn asks her to gain some sexual experience in order to produce a more ‘realistic’ story, Yuma embarks on an unlikely journey within Tokyo’s underbelly, where she’ll find adventure, generosity, and humanity.

“In crafting this unique Bildungsroman, HIKARI finds a special style of filmmaking. Blending Japanese pop with humour and bold tenderness, she draws an honest portrayal of disability, brilliantly brought to life by the amazing performance of first-time actress Mei Kayama.”

Here we are on December 31, so it’s time to go over my list of the films I watched in 2019. I didn’t watch as much as I hoped – the total count is 263 titles – but I tried my best to expand my cinematic knowledge as best as I could. In addition, I’ve added the list of films I’ve seen this year that were directed by women, as well as the results of another fun thing I did called the Watch Four Films Challenge. Enjoy!

1920-1924: The Three Musketeers

1930-1934: An American Tragedy; Blondie Johnson; Blood Money; The Cabin in the Cotton; Cavalcade; From Headquarters; Honor Among Lovers; If I Were Free; Jewel Robbery; The Kennel Murder Case; Le Million; The Song of Songs; They Call It Sin; The Thin Man; This Man Is Mine; Transgression

1935-1939: Confessions of a Nazi Spy; Craig’s Wife; The Ex-Mrs. Bradford; Fast and Furious; Fast and Loose; Fast Company; Front Page Woman; The Hunchback of Notre Dame; In Name Only; The Irish in Us; Marked Woman; Merrily We Live; Sabotage; The Walking Dead; The Women; You Can’t Have Everything

1940-1944: A Girl, a Guy, and a Gob; The Amazing Mrs. Holliday; It Happened at the Inn; Johnny Eager; Night Train to Munich; Our Town; Our Wife; Panama Hattie; Parachute Battalion; Reap the Wild Wind; They Met in the Dark; Turnabout

1945-1949: Bedlam; The Boy with Green Hair; Dead Reckoning; Force of Evil; The Ghost and Mrs. Muir; House of Strangers; Isle of the Dead; The Loves of Carmen; Nobody Lives Forever; La Otra (aka The Other One); Railroaded!; The Velvet Touch; White Heat

1950-1954: All About Eve; The Asphalt Jungle; The Belle of New York; Bright Road; Carmen Jones; Crime Wave; His Kind of Woman; Hollywood Story; I Love Melvin; The Jackie Robinson Story; Julius Caesar; The Killer That Stalked New York; M; Pagan Love Song; Rancho Notorious; 711 Ocean Drive; Show Boat; The Tattooed Stranger; Texas Carnival; The Turning Point; Two of a Kind; Untouched

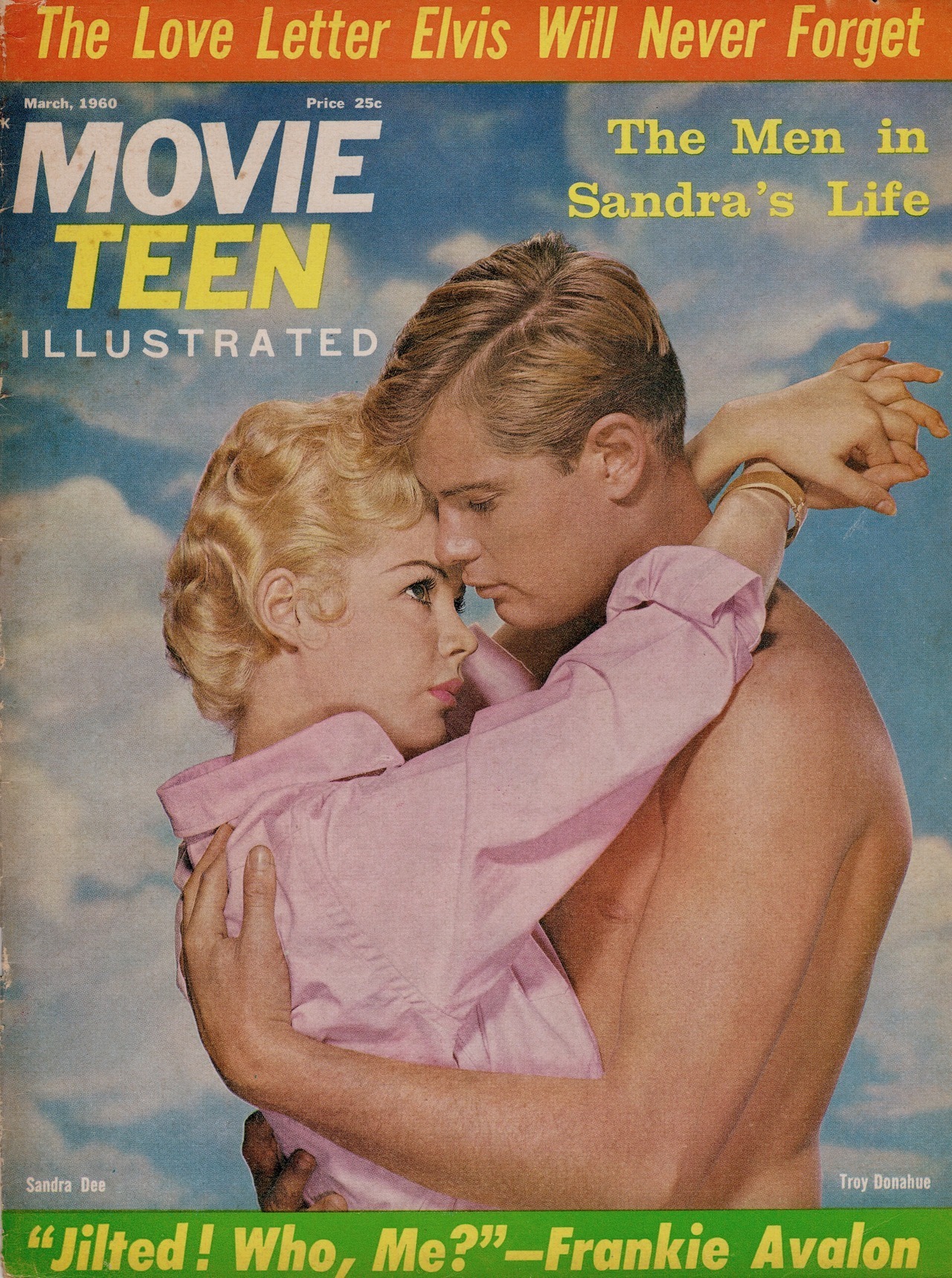

1955-1959: The Black Scorpion; Macabre; The Opposite Sex; Over-Exposed; Pillow Talk; A Summer Place; 12 Angry Men; Up Periscope; Women’s Prison

1960-1964: Carnival of Souls; Gypsy; The Honeymoon Machine; Love with the Proper Stranger; Midnight Lace; The Pink Panther; Seven Days in May; Something Wild; Splendor in the Grass; Where the Boys Are

1965-1969: Ebirah, Horror of the Deep (aka Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster); Funeral Parade of Roses; The Gay Deceivers; The Glass Bottom Boat

1970-1974: The Devils; Dracula A.D. 1972; Klute

1975-1979: The American Friend; Between the Lines; The Brood; Escape from Alcatraz; The Late Show; Marathon Man; Picnic at Hanging Rock; Shivers

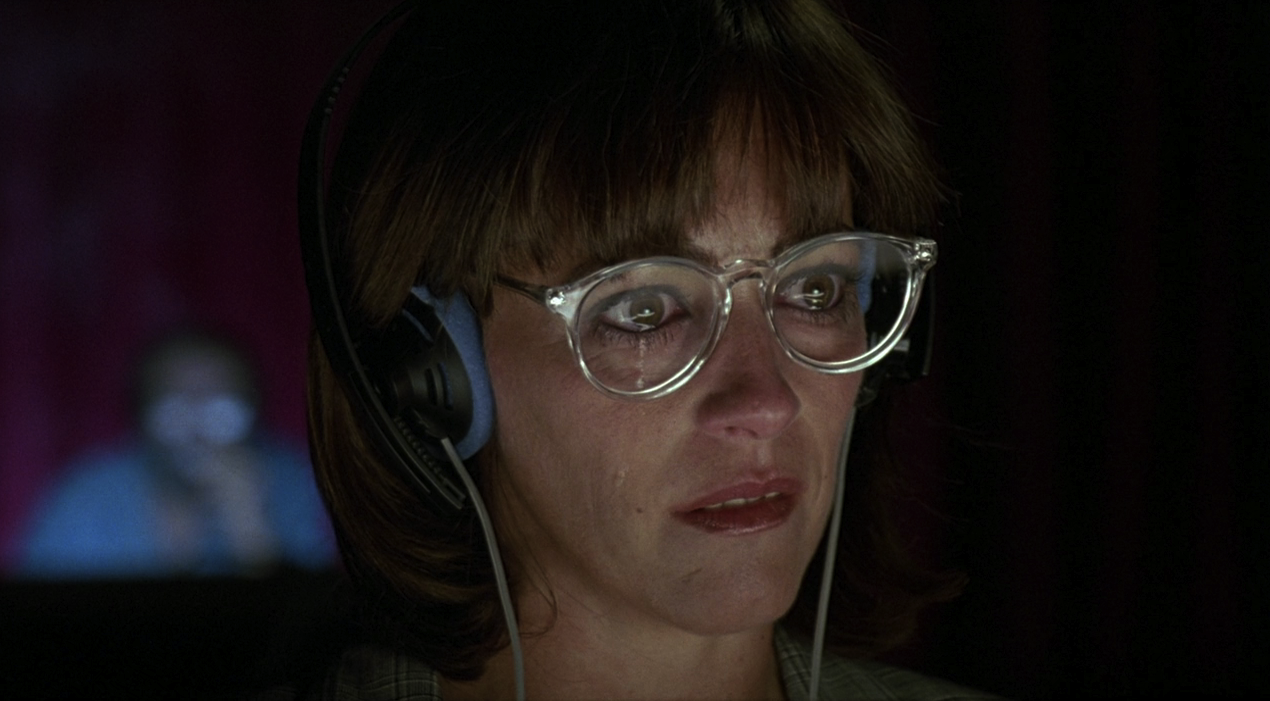

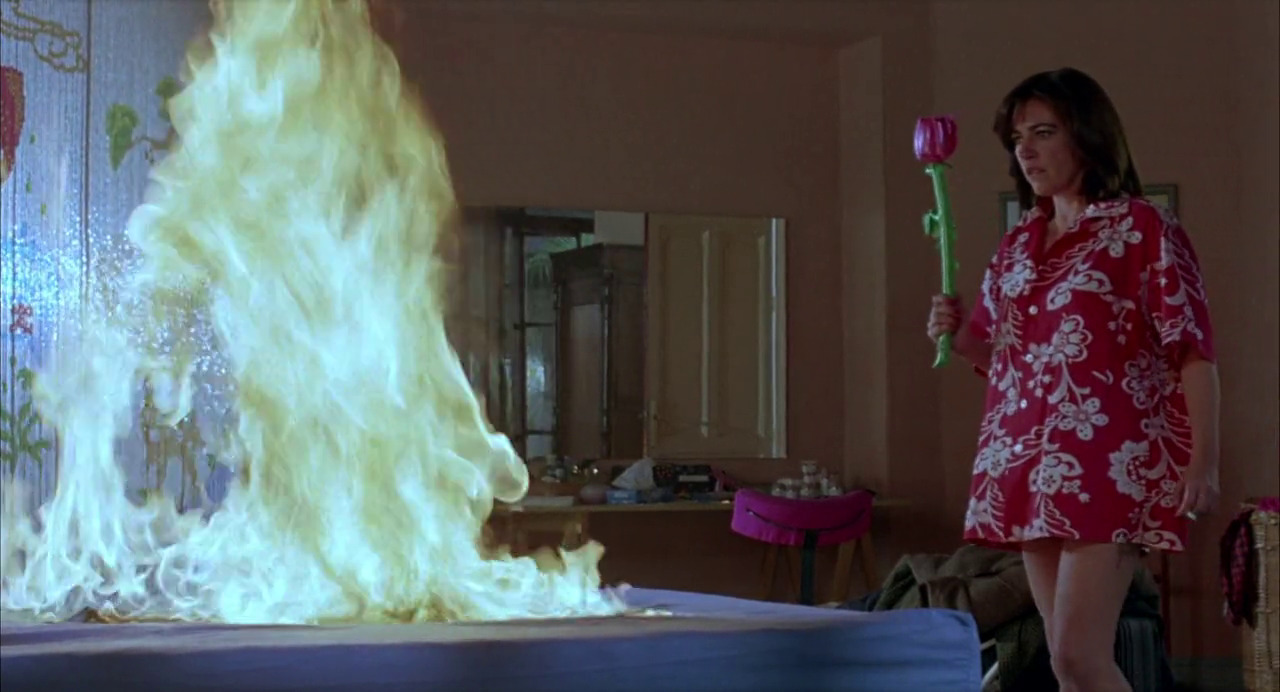

1980-1984: Black Candles; Bloody Birthday; Dark Habits; The Dead Zone; Fear City; Flashdance; Inferno; The King of Comedy; Labyrinth of Passion; Pepi, Luci, Bom; What Have I Done to Deserve This?

1985-1989: Child’s Play; Cocktail; Hairspray; Law of Desire; Matador; Pumpkinhead; The Running Man; Sorority House Massacre; Steel Magnolias; Witness; Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown

1990-1994: Candyman; The Crow; Days of Thunder; High Heels; Home Alone; In the Line of Fire; Kika; Misery; No Fear, No Die; Philadelphia; The Silence of the Lambs; Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!